STEPHEN BROWN BIO

STEPHEN BROWN

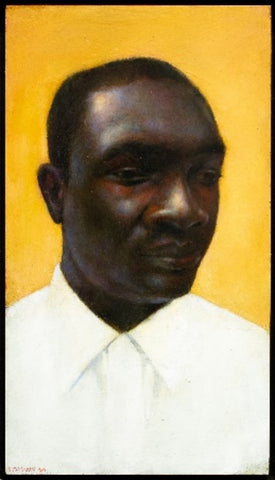

(LEFT) Self Portrait in Dark Shirt, 2008-2009. Oil on panel, 7 1/4 x 3 1/2 inches

(RIGHT) Boots, Oil on Birch panel, 18 1/2 x 15 3/4 inches

"The small, powerful, and compelling paintings of Stephen Brown confront one with an unswerving directness and unnerving sense of inevitability. Brown's paintings are refreshingly and confrontationally figurative. The actuality of paint gleam and glint and the paintings are fulgent, the figures within them are perceived as though magically lit from within. The paintings project reality through the masterly manipulation of plasticity. To achieve a sense of monumentality using so small a scale reveals the achieving hand of the veritable artist." American Academy of Arts and Letters, May 1994

ABOUT

Stephen P. Brown was a realist painter whose art was filled with vivid light seemingly illuminated from within. His subjects were his family, friends and everyday surroundings, but one could argue his complex surface layers attracted equal fascination. Also highly regarded as a teacher, his legacy is an inspiration to those lives he touched in his chosen home of New England.

Brown was born in Greely, Colorado, in 1950. His father was a baker, and his mother, a homemaker at the time, was also an amateur artist. Besides her influence, the light and grandeur of the western landscape were among his main impacts as a young painter. After graduating with a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Colorado State University in 1972, he attended the prestigious Skowhegan School of Paining in Maine that summer. There he met and studied with the figurative painter Alice Neel, who encouraged him to move to New York City.

With just a few dollars in his pocket, he moved in with a friend on the Bowery. In 1973 he convinced Neel she needed a studio assistant. For several years he helped her transfer wall drawings to canvases, model for paintings, and among other things, critique her work. (Upon her insistence, with just one veto between the two of them, she would tear a drawing in half.) Their relationship had a profound influence upon his portraits. Brown's paintings "confront one with an unswerving directness", as stated in the 1994 exhibition catalog of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, when he won the Academy Award in Art in New York City.

In 1975, he returned to Colorado for treatment of a reoccurrence of Hodgkin's disease he developed when he was fifteen. Because of this constant health threat, painting became a catharsis. His friends and family knew this vulnerability drove his artistic passion and energy, and that he rarely stopped painting to relax.

With his cancer in remission again at the age of 26, he returned to New York City. Soon, he enrolled in graduate school at Brooklyn College, City University of New York. There he studied with world renowned artists Philip Pearlstein, Lennart Anderson and Lois Dodd. It was here that he met and later married fellow student Gretchen Treitz. While in school, he had his first one man exhibit in 1978 in New York City at the Bowery Gallery in SoHo. Visitors to the opening were greeted by a frantic Brown on a ladder still painting his life size self-portraits, still lifes, and nudes. Even back then, he cropped his large canvases, only later realizing he needed the space around his subject, he would hand sew the piece back on. Also, during this time, Brown was involved with the Alliance of Figurative Artists in downtown, where artists met to discuss big ideas in reaction to abstraction and pop art. Besides Neel, Pearlstien and Dodd, friendships were born there with other realists such as Paul Geroges, Leland Bell, Gabriel Laderman, Rackstraw Downs and Paul Resika.

After marrying in 1982, Brown had a one man show uptown at the Alex Rosenberg Gallery. These large-scale paintings of self-portraits, friends, still-lifes and nudes were well received. After several shows at Rosenberg, he experienced the success and pressure of selling on 57th street. One day, in 1986, he impulsively carried five pastel cityscapes under his arm and walked boldly into Allan Stone Gallery. Just as spontaneous, Stone reacted favorably and accepted Brown into his stable of artists. Stone appreciated the intense surface process. Thus began a decade of a friendly relationship with one of the great art dealers of the late twentieth century. Brown not only exhibited in Stone's 86th St. gallery, but played tennis with him over the years as well. Several of Brown's paintings are in Stone's private collection. Also during this time, friendships were formed with artists, among others, such as Raphael Soyer, Altoon Sultan, Joe Groell, Allan D'Arcangelo, Bob Henry, Chris Semergieff, Mark Pehanic and Wayne Thiebuad. While visitng Soyer's studio in 1985, Brown painted a striking portrait of him as they discussed American realism. By teaching part-time at Parsons and Studio in a School, he was able to paint and exhibit regularly during this time.

Because their teaching schedule allowed, Brown and his wife left New York City every summer for landscape painting adventures out west. They meandered all over the Rocky Mountains in search of the perfect location to paint, and only after found, would they set up their tent. Painting landscapes side by side, they usually chose a national forest for privacy, as they felt their French easels and umbrellas attracted too many spectators. Ranchers, truck drivers and fishermen became their wandering friends. Inspired once again by the expanse and luminosity of the western vista, Brown was in his element. As in all their artistic work, Brown and his wife were each other's best critic; painting the strongest light early in the morning and late evening allowed for mid-day analysis of his oils, and her watercolors. Dealing with the elements proved difficult and sometimes comical on many occasions. Bird droppings on watercolor paper and dusty earth on oils required cropping and rinsing. Even so, these summer journeys were very productive and lucrative for both.

After fifteen years in the city, and well established in the art world, they decided it was time to seek other surroundings and job opportunities. They agreed whoever received the best teaching offer, they would relocate there. In 1987, Gretchen was offered a one year adjunct position teaching art at Pennsylvania State University. They were thrilled to experience a totally different environment. They rented a house on a dairy farm, totally encircled by Holsteins. It was this bucolic American heartland that was the inspiration for new subject matter for Brown. Cows, horses, silos, and rolling fields, all bursting with light and energy, became for him a reunion to his rural past. The fortitude of the dairy farmers matched his own moral fiber and many became his kindred friends, often referring to them (and his father), as "salt of the earth". Painting the farmlands of the central Pennsylvania mountains afforded him the opportunity to continue exploring his love for the dialogue between long, transparent shadows and color-filled light on forms. Brown's process of working over the surface, scraping and building his strokes, unintentionally became his subject; the compulsive, creative energy of his technique gave his paintings a magical feeling. His craving for artistic sustenance was constant. He created a very large body of work, especially landscapes, during this significant period.

The following year, in 1988, Brown was offered a tenure track position at the Hartford Art School, a college within the University of Hartford. Here he found his calling as a teacher. His personable manner, and intellect, matched by his strong exhibition record, quickly attracted students from all over the United States. He was responsible for increasing the number of painting majors, improving his department, developing a Graduate Program, and expanding the Art School's reputation.

In 1989, his son Rushton was born, and brought a new level of intensity to his art. Because of this overflowing love, Brown embarked on two decades of painting portraits of his son. Family life also revolved around exhibits of both Stephen and Gretchen, their studio time, trips to New York and Boston, museums, galleries, and of course teaching by both parents. In 1990, Stephen was awarded the honor of a one person exhibition from winning the Connecticut Vision Exhibition at the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury. The show opened at the museum in the fall of 1991 and included "a series of cows-in-the meadow with genuine expressiveness, empathy, and a divine...humor" (from the catalog essay.) Along with other large scale paintings of animals, figures and still lifes, the exhibit was well received. Shortly afterwards, other museums and galleries in the New England region exhibited his work, including the New Britain Museum of American Art, Paesaggio Gallery, Hofstra Museum, New York Academy of Art, National Academy of Design, the Joseloff Gallery, Allan Stone Gallery, and many others around the country.

Brown's daughter, Hannah, was born in 1992. She was the apple of his eye, but he ended up painting only one portrait of her. Life soon became a juggling act of painting, teaching and family. In the same year, the Browns bought an eighteenth century farmhouse in Massachusetts, equipped with fields, a pond, and three barns. Two of the barns were renovated into studios with northern windows, skylights, and heat. In 1994, Stephen was awarded the prestigious Academy Award in Painting at the American Academy of Arts and Letters in New York. As fate would have it, his seating assignment on the Academy stage was next to George Tooker. Thus began a long term friendship, with Brown painting Tooker's portrait, and many visits to each other’s studio. Several dealers and museums courted his work from that renowned exhibition, including Forum Gallery in New York. After several group exhibitions at their prominent galleries in New York and Los Angeles, his first one person exhibit at Forum NY was in 2000. Stephen's work had transitioned from large scale cows to more intimate figures, still lifes and landscapes. The show was a huge success, attracting both reviews and sales. He continued to exhibit there, and at regional and national museums, including the National Academy Museum, the Arnot Art Museum, and the Long Beach Museum of Art.

Brown's second one person exhibit at Forum Gallery was in 2004. This show also traveled to their Los Angeles gallery, Robert Fishko, the notable director of both, was an enthusiastic ally, Fishko was instrumental in not only marketing Stephen's work, but disseminating it out into the world. It was Fishko's belief in Stephen's talent that secured his paintings in many private and public collections. To quote the 2004 catalog essay, "there is an honesty and clarity in Brown's approach...which makes the experience of viewing his work intimate. His paintings are small in size...but have emotional power... "

Beginning in 2005, Brown's health deteriorated, beginning with a stroke, and later a pulmonary embolism. Even though his work was temporarily diverted, his passion for painting drove him deeper into his work when his health improved. In 2006, he began a series of paintings of trees. While driving home past an orchard on his road, he noticed a pear tree in the exact shape of his stroke on the x-ray he had brought home. He instantly knew that the pear tree's pruning and regrowth duplicated the shape in his brain. Thus began his series of paintings and pastels of this same pear tree, a catharsis of healing. Writing in the 2012 "Legacy" catalog, colleague and dear friend Walter Hall describes "These paintings are about rising above the daunting forces that threaten or obstruct one's way; both defiant and life-affirming, the vitality of the new branches, shooting up from the gnarled, suffering trunks, presents a noble and exhilarating image of the irrepressibility of the will to live." Hall continues, "Aside from his talents as a painter, it is a tribute to his innate wisdom and depth that, by instinct, he focused only on the things that matter and endure. Stephen's paintings have universal resonance because these were the values that interested and moved him. In the context of academia, and in the art world itself, categories often matter more than they should. It always impressed me that his view of painting was unbounded by artificial distinctions; it was broad in scope, concerned only with essentials and authenticity, preoccupied with expressing the deep realities he felt. ...Painters and critics admired his mastery of touch, the poetry of his vision, his skill at pictorial orchestration, and his mastery of light."

In 2008, Brown was diagnosed with lung cancer, even though he never smoked. After a year and a half of treatments, hospital stays, and teaching from a wheelchair, he succumbed to the disease in 2009. Even in poor health, his compulsive desire to paint occupied him until the end. Door knobs, pears, and trees were the last subjects he invested himself into, still generating so potent a vision of life into his art.

____________________________________________________________

STEPHEN BROWN

1950 Born in Greely, Colorado

1972 Bachelor of Fine Arts, Colorado State University

1972 Skowhegan School of Painting and Drawing

1980 Master of Fine Arts, Brooklyn College, City College of New York

1988-2009 Professor, Hartford Art School, University of Hartford

2009 Died in Hartford, Connecticut

SELECTED EXHIBITIONS

2018 Portraits Exhibit, Washington Art Assoc. & Gallery, Washington, CT

2016 Still Life, Gallery North, Setauket, NY

2012 Stephen Brown: Legacy. The Hartford Art School. Hartford, CT

2009 The 184th Annual: An Exhibition of Contemporary American Art, The National

Academy of Design, New York, NY

2009 A Figural Presence, Alva de Mars Megan Chapel Art Center, Saint Anselm College,

Manchester, NH

2009-2003 Faculty Exhibition, Joseloff Gallery, Hartford Art School, University of Hartford, CT

2008-2009 As Others See Us: Contemporary Portrait, Brattleboro Museum of

Contemporary Art, VT

2008 Here's The Thing: The Single Object Still Life, Katonah Museum of Art, Katonah,

NY

2007-2008 About Face: Portraiture Now, Long Beach Museum of Art, Long Beach, CA

2007 The 182nd Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Art, The National

Academy of Design, New York, NY

New England Now, Paper/New England Gallery, Hartford, CT

2004 Stephen Brown: Recent Work, Forum Gallery, New York, NY

Stephen Brown: Recent Work, Forum Gallery, Loa Angeles, CA

2003 178th Annual Exhibition, National Academy of Design, New York, NY

Contemporary Works on Paper, Forum Gallery, New York, NY

2002 All Outdoors: Landscapes in Oil, 100 Pearl St. Gallery, Hartford, CT

2001 176th Annual Exhibition, National Academy of Design, New York, NY

Identities: Contemporary Portraiture, New Jersey Center for Visual Arts, Summit,

NJ

2000 Recent Work, Forum Gallery, New York, NY

1999 New Realism for a New Millennium, Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester,

NY

Contemporary Still Life, The Contemporary Art Center of Virginia, Virginia Beach,

VA

1998 It's Still Life, Forum Gallery, New York, NY

1997 The Boston International Fine Art Show, At the Castle, Boston, MA

US Artists at the 33rd Street Armory, Philadelphia, PA

Still Life Painting Today, Jerald Melberg Gallery Inc., Charlotte, NC

New Faces, Forum Gallery, New York, NY

Eleven Faces: A Portrait Show, The Painting Center, New York, NY

1996 New Acquisitions, Albany Museum, Albany, GA

Exactitude, Forum Gallery, New York, NY

1995 47th Annual Academy Purchase Exhibition, American Academy of Arts and

Letters, New York, NY

Pencil to Paper, One West Art Center, Fort Collins, CO

New Looks, Forum Gallery, New York, NY

Invitational, Forum Gallery, New York, NY

1994-1995 Intimate Views, Westfield State University, Westfield, MA

1994 Newly Elected Members and Award Recipients Exhibition, American Academy of

Arts and Letters, New York, NY

46th Annual Academy Purchase Exhibition, American Academy of Arts and

Letters, New York, NY

The 169th, 167th, 165th, 163rd Annual Exhibition, National Academy of

Design, New York, NY

1993-1994 Stephen Brown: Portraits: Lands and Friends, New Britain Museum of

American Art, New Britain, CT

1992 Stephen Brown: One Person Exhibition, Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, CT

AWARDS, GRANTS, HONORS

2007 Full Professorship Hartford Art School, University of Hartford, CT

2001 The Gladys Emerson Cook Prize National Academy of Design, New York, NY

1999 Elected Academician National Academy of Design, New York, NY

1994 Academy Award for Painting American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York,

NY

Benjamin Altman Award (for a landscape done by an American Citizen),

National Academy of Design, New York, NY

1991, 1993 Coffin Grant (competitive grant awarded to University of Hartford faculty),

University of Hartford, CT

1992 One Person Exhibition Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, CT

1979 Yaddo Fellow Saratoga Springs, NY

Resident Milay Colony for the Arts, Austerlitz, NY

1978 Charles B. Shaw Painting Scholarship

MFA Graduate Program, Brooklyn College, City University of New York, NY

COLLECTIONS

Hofstra Museum, Hempstead, NY

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MO

New Britain Museum of American At, New Britain, CT

National Academy of Design, New York, NY

D’Amour Museum of Art, Springfield, MA

Albany Museum of Art, Albany, GA

The Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, CT

The Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY

Seven Bridges Foundation, Greenwich, CT

The Freedman Gallery at Albright College, Reading, PA

____________________________________________________________

Nebraska Wesleyan University

Elder Gallery features paintings by artist Stephen Brown

Published

Thursday, November 4, 2021

Elder Gallery features paintings by artist Stephen Brown

The work of the late realist artist Stephen Brown will be featured at NWU’s Elder Gallery later this month. The exhibit is entitled The Aching Beauty of it All: Paintings by Stephen Brown. This will mark the first time the artist’s work has been exhibited in Nebraska.

The exhibition features over 70 paintings spanning the late artist’s career. Born in Greeley, Colorado, Brown spent his career in New York City and New England. He received The Academy Award for Painting from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, The Gladys Emerson Cook Prize from The National Academy of Design, and the Benjamin Altman Prize for a landscape done by an American citizen from the National Academy of Design. Brown is the subject of numerous one-person museum and gallery exhibitions.

The exhibit was curated by Associate Professor of Art David Gracie, who was Brown’s student at the Hartford Art School. Gracie also produced a catalogue and essay for the occasion. The exhibit opens on November 9 with a reception on November 12 from 5-7 p.m. in Elder Gallery, located inside the Rogers Center for Fine Arts at 50th Street and Huntington Ave.

The Aching Beauty of it All: Paintings by Stephen Brown, an essay by Associate Professor of Art David Gracie

I was nervously awaiting my professor’s arrival on the first day of Painting Composition class at the Hartford Art School in the late 1990’s. With one foot out the door, Professor Stephen Brown appeared and waved his arms directing us outside. The weather was beautiful out. The edge of late summer heading into a New England fall. Stephen’s instructions were to compose a picture with sticks, leaves, acorns, or whatever was lying about on the grass and ground near the art building. I didn’t understand what Stephen was talking about as he spoke passionately about movement, balance and the framing edge, but I went to work regardless and in earnest. I can still picture the look in his eyes. I can still hear the excitement in his voice. When Stephen visited my plot of lawn he adjusted a stick a quarter inch, raised another, tossed still another. He stepped closer in and then back. Stephen was seeing the world as a painter.

Stephen Brown walked a line between art and life. Painting is how he took in the world and marked time. Reconciling the aching beauty of life within the framing edge of his paintings was his aim. Painting was Stephen’s affirmation of being alive.

Stephen wanted to at once announce the sometimes crude and other times remarkable plasticity of oil paint while holding reverence for the landscapes he lived in, the people he loved, the bric-a-brac that surrounded him. This friction of medium / subject / art / life can, at special moments, create transcendence. As his student, Stephen often referred to these moments of transcendence as “magic.” He taught me that you can never predict when this “magic” will happen until it arrived. It would hit you like an epiphany.

When making his small paintings Stephen would often work with the painting in his lap. He described this as “almost being on top of or inside of it.” Having the painting orientated this way made it clear that it was both an object and an image. While holding the painting in his lap, he would use jeweler’s magnifying goggles to peer into the depth of the surface. He would build opaque passages, glaze with transparent colors, and then scumble translucent paints on top. Always mindful not to fall into a system, he would sand and scrape to reveal passages into earlier layers. The subtractive element allowed earlier moments of the painting’s self-narrative to come to the surface alongside newer marks. Like riding a wave, Stephen painted with intuition and skill as each move flowed into the next move. With each seeming final decision another problem was presented. At a certain point, on the crest of the wave, he painted for the moment the inertness of the painting sparked to life with the energy of the world.

Stephen built his paintings with only a rough blueprint in his mind’s eye. He would build them up and then tear them down. He would scrape, sand, cut, glue, glaze and repeat. This process was not a straight line. He was coaxing something out of the ether. Stephen understood the weight and privilege of participating in the history of painting. In class, he recalled how his mentor and friend Alice Neel only really liked one artist: Francisco Goya. I think Neel’s narrowness fueled Stephen to be open to myriad ways of working, and “openness” in turn allowed Stephen to always be searching within his own paintings.

As I begin my seventeenth year of teaching at Nebraska Wesleyan University, I can reflect on how each of my students is taught Stephen’s way of seeing the world as a painter. That same way of seeing which I first witnessed on a fall day back in Hartford, CT.

For Stephen, the possibility of the image in his paintings was always in flux to the very end. He would take dried bits of paint and glue them to the painting surface and incorporate them into the existing surface. He would often find the framing edges well into the painting process and redefine them with tape and a table saw. In class, he described gluing a wood strip to the top of his painting to give more air and space, to let the work breath. The active surface, full of different levels of resolution all at once, is an analogy for the world moving underneath our feet.

With his process being additive and subtractive, concealing and revealing, the paintings have a complicated relationship to time. Many different marks, passages and edits, are different moments in the making. You will see a gestural brush mark from early in the process next to a jeweled passage that has been scraped with a razor blade. Like a person standing in front of you, an object on the counter, or a landscape captured by your gaze, you sense the history leading up to the point in time when you are now beholding his paintings. The details and order of that history are not clear, but you are convinced of its presence.

Color in Stephen’s paintings can simultaneously stand on its own merit while, at the same time, be seamlessly integrated into the full image. He understood being a realist painter doesn’t simply mean that you copied what was before you. The paint color itself is equally real and has its own material, conceptual and expressive potential. Much has been written about the light in Stephen’s work. I view Stephen’s use of light as architectural supports; the genius of the work is his use of color. Many times in class Stephen would walk up to my easel and say, “make that a better color.” He did not mean the color I was mixing wasn’t an exact match for the one I saw in the class still life, he meant that I should keep searching for the extraordinary.

For Stephen, his own laborious and obsessive painting process could be exhausting. He learned that if he “put all of his eggs in one basket” it would take an emotional toll. Through experience, Stephen developed a way of working where he would have many paintings going at once. He would set an egg timer and paint for a frenzied period of time. At the chime he would switch paintings and reset the timer. This, he said, kept him concentrating on the most important things: the parts that would make him happiest. Reflecting now, I believe this process was not just to break obsessive tendencies. The process allowed more of the life he loved into the studio. With the painting in his lap, peering into the surface, he painted with his entire history and his love at the point of his brush.

As I begin my seventeenth year of teaching at Nebraska Wesleyan University, I can reflect on how each of my students is taught Stephen’s way of seeing the world as a painter. That same way of seeing which I first witnessed on a fall day back in Hartford, CT. Many of my former students plan to come back to campus to see Stephens’s show. And on it goes.

This exhibition has been made possible by the work, wisdom, and generosity of Gretchen Treitz-Martin. I am and will be forever grateful.

David Gracie, Associate Professor of Art, Nebraska Wesleyan University | 2021

____________________________________________________________

A CONVERSATION ABOUT STEPHEN BROWN’S PAINTINGS

Posted on January 16, 2022 by matt ballou under Life

From a conversation between David Gracie and Matt Ballou on January 15, 2022 in Lincoln, NE. Editing for clarity and length.

Stephen Brown – Ruhan (left) and David (right). Oil on wood. 2000.

Matt: The installation of this exhibition isn’t chronological. What was the idea? That there would be pictorial themes or color themes?

David: That’s right. It’s not chronological, but there are some pieces that are grouped together, you know? There are pictorial themes, and I think that kind of like went with the territory, with the type of painting he was doing at any particular time. So there’s landscapes, still life, portraits, and figures.

This exhibition is a little bit different because there are some older works that are kind of out of context, but I thought they were worth putting in just because of the spirit of the show. So there are two rooms of main, finished works, and then there is also the room of only unfinished work.

Details of Ruhan and David.

David: These two real highlights of his portrait painting. I love these two paintings. If I could have gotten the George Tooker portrait, it would have probably been my favorite one. I remember when I had him as a teacher, he talked about that George Tooker painting as being the best portrait he’d ever done.

I think the different conventions (landscape, portrait, still life), you know, they all kind of add up to the same type of thing. But this (show) is a result of the work that was available. And also, in some ways, this is the way he would have done it (a range of whatever was available at the time). Because, when he had shows, they would be called just, like, “NEW WORK.” And then there would be some thematic shows that the galleries would put on, like Alan Stone Gallery and those 57th street galleries that would do still life or portrait shows. Because this work is all coming from Gretchen, his widow, there are 16 portraits of his son, Rushton.

Gracie holding Rushton in Bedroom, Massachusetts oil on wood, 2009, verso of Portrait of Gretchen, oil on wood, 2009

Stephen Brown – Unfinished Light Bulb. Oil on wood. 2009.

Some of these works he was doing when I was a student. He was talking about Van Gogh’s boots and that Diamond Dust Shoes essay, the Fredrick Jameson one.

Matt: I love the shadow here.

David: I love the fact that the boots can’t sit there. There’s not enough space. They poke out into our space because like that line doesn’t make room for the heels. The heels couldn’t live there.

Matt: There’s a simultaneous compression and expansion to it.

Detail of Boots, oil on wood, 2002, by Stephen Brown.

Matt: I feel like there’s like a luminous opacity in so many of these. It reminds me of some passages in Paul Fenniak’s work. There’s a sense of it being so thick but also almost phosphorescent…

David: You can see that it (Brown’s approach at times) was very much like Lennart Anderson. And then over the years, you know, he would [shift influences and interests], so he went through these different, completely different phases, you know? And he was part of a whole group of artists that were meeting together (in the 70s and 80s), the Alliance of Figurative Artists.

Details of Stephen Brown paintings – Unfinished Horizontal Tree, oil on wood, 2009 and Unfinished HAS Student, oil on wood, 2009.

Matt: What’s the timeframe on making these works? Did he have them scattered around the studio and he was working on them over months and years?

David: Yeah, off and on like that. He would work on the paintings for a very long time. That’s how he worked, though; he would do forty paintings at a time. There’s a lot of on these, too.

Matt: I mean, the thickness of that! There are so many layers of glaze… almost like it’s got the presence of light and flesh at the same time. That quality.

David: He would pile it on and then sand it off – power sand – the surfaces down. He worked in a barn, too. You can see it in the other room (featuring unfinished works), like, different stages of development. Also, on this Gillespie (portrait) in this room.

David Gracie pointing out some details.

Importantly, he lived near Gillespie in Massachusetts, and he was really into Hans Holbein and Spanish still life painting. Towards the end of his life, he was really into self-portraits. He also painted a bunch of trees, like these weeping cherry trees.

When I was there (Hartford School of Art) he was the kind of guy who would get up every morning at 5:00 a.m. to play tennis. He was strapping, super energetic, and full of exuberance when I knew him. I knew him from ‘97 to 2002 and then kind of lost touch with him. Then he got sick. Some of the students he had after my time said he taught in a wheelchair.

David: Gretchen told me how sometimes she would go out to his studio and say something about a painting, like, “Oh, I really like this part.” And then she’d go to bed, only to hear the power sander start… he’s just sanding that part off!

So, it’s like these things are so precious, but at the same time he’s so willing to just power sand that shit off! There’s such precision and detail but none of it was safe. On one hand he’s got all of this chaos going on – some of these look like they were laying on the floor and he’s stepping on them, you know? But then you go over into the other room and see some of those perfect portraits with incredible frames, and the contrast is so intense.

Details showing the edges of unfinished Stephen Brown self portraits, 2009.

Matt: But then you think, did they exist in that (chaotic) state at some point? You know what I mean? I think they probably did.

David: Yeah, I would say they did exist in that state at some point. And you can see some that are almost there but not quite…

Matt: Because it seems to me that the cohesion that the finished ones have – some of these more refined ones – that cohesion is based on it having come through that unsafe process. I do like that a lot of these things require a sitting period. They’re not alla prima at all. The accrual has to happen.

Matt: Is this show kind of like a labor of love for you? The essay you wrote is great, and I especially like the title, the poetry of the title (“The Aching Beauty of It All: Paintings by Stephen Brown”). You know, it’s almost like something that he wouldn’t have done for himself. But that’s the way he talked about painting, right? Like, the feeling in the moment of painting, in the moment of observation.

David: Yeah. I mean, that’s what his painting was about. It was in the painting. He didn’t write shit about it. Writing was too literal. So I was self-conscious about [writing about it] because it is almost like, too much, too earnest or something.

Details of Stephen Brown – Onion. Oil on wood, 2006.

Matt: But that’s kind of the way it all is!

David: Yeah, the whole thing is so earnest. But it’s not like some of the over-the-top, romantic painters out there taking themselves too seriously. He wasn’t self-centered.

Matt: It’s straight. There’s no affectation. That’s the difference. It’s not trying to be something other than what it is.

David: I just wonder if other people see it as if there is too much, of it being on the edge of too earnest. Perhaps there is some affect in that way.

Matt: Well, that’s half my problem over the last 15 years: with all the horrible things going on in the world, can I believe in the earnestness of this act (painting, art making)? But the sense of living in the work is so present here; obviously he’s worked on some of these for hundreds of hours, potentially. So much evidence of time and attention.

Detail of Stephen Brown – Still Life with Apple Blossoms, oil on board. 1997.

David: With the amount of sanding and number of layers going on we have no real idea how he got from A to Z. Maybe I have a closer idea of how they work than someone generally, but still, I’m not quite sure. I think his works are hard to unravel in terms of how they feel.

But that was his thing.

Matt Ballou is an artist and writer who teaches at The School of Visual Studies at the University of Missouri.

David Gracie is a painter and professor at Nebraska Wesleyan University.

“The Aching Beauty of It All: Paintings by Stephen Brown” will remain on view at Elder Gallery in Nebraska Wesleyan University’s Rogers Fine Arts Building at 5000 St. Paul Avenue, Lincoln, NE through January 30, 2022

____________________________________________________________

Lincoln Journal Star

Elder Gallery exhibition pays tribute to figurative painter Stephen Brown

- Kent Wolgamott

- Jan 14, 2022 Updated Feb 25, 2022

Figure 2 "Brooklyn in Spring" is an oil on wood painting by Stephen Brown from his exhibition "The Aching Beauty of It All" now on view at Nebraska Wesleyan's Elder Gallery.

Putting together “The Aching Beauty of It All: Paintings by Stephen Brown” was a labor of love for Nebraska Wesleyan art professor David Gracie, who is paying tribute to his teacher with the Elder Gallery exhibition of Brown’s paintings.

Gracie, who studied painting with Brown at Hartford Art School in Connecticut, traveled to the Kentucky home of Brown’s widow Gretchen Treitz-Martin, selected some 75 works, brought them back to Lincoln in a van.

With Wesleyan colleagues, Gracie put together a catalog, with a bio written by Treitz-Martin, and effectively hung the show of small paintings in the gallery’s three large spaces, showcasing the variety in Brown’s subject matter, the repetition of his figurative subjects and, in a space devoted to 30 works that were unfinished at the time of Brown’s 2009 death, his artistic process.

Primarily a figurative painter, who studied and worked as a studio assistant with Alice Neel, Brown used his wife, son Rushton, friends and fellow artists like magic realist painter Gregory Gillespie as his models.

As a traditionalist whose career began in the ‘70s, Brown also painted still lifes, interiors and landscapes.

But those subjects, whether the northern Colorado landscape of “Near Home” or “Pawnee Butte,” the rooftops of Brooklyn or the doorknobs that he repeatedly painted near the end of his life were all deeply connected to the artist, a Greeley, Colo. native who worked in New York City before moving to New England to teach at Hartford.

“Everything he’s done is about connecting his love of painting with everything he loved in life,” Gracie said as we walked through the galleries. “It’s an optimistic thing that, I think, is appropriate for this moment.”

The show of Brown’s paintings is appropriate for the moment for another reason. Figuration has, of late, returned to contemporary painting and work by Brown’s mentors and colleagues like Wayne Thiebaud, Lois Dodd, Philip Pearlstein and Rackstraw Downes is being examined under a new light.

Brown’s work deserves such a re-examination and, with close viewing, gets it via “The Aching Beauty of It All,” and Gracie’s illuminating catalog essay.

That examination instructively begins with the unfinished paintings, propped on shelves at easel-like angles.

Showing the masking of the subject matter, the layers of paint, the variation in looks at the same subject – including an pair of self-portraits, the unfinished works display something of a skilled artist at work, patiently striving to capture the combination of color, line, depth and luminosity that creates painting “magic.”

Other pieces when seen from inches away, reveal Brown’s techniques of scraping, sanding, layering and gluing in bits of dried paint to create a surface alive with texture and light while other figurative pieces explore the expression of their subjects, and, through a few pieces years done, Rushton growing up.

Treitz-Martin is the subject of multiple paintings, including the exhibition’s nudes – that demonstrate that Brown was a superb, classic-style painter. But even when provocatively posed, the nudes aren’t exploitative, hence the title “Gretchen, Leg Up.”

Other pieces, like “Boots” seem odd. That is until Gracie explains that Brown loved Vincent Van Gogh, who painted his boots. So Brown’s take on the battered worn footwear is his nod to Van Gogh, via subject matter rather than aping his unmatchable painting style.

With 75 pieces, there’s a lot to take in in “The Aching Beauty of It All.” I’ve made two visits to Elder since the show has been on view and will likely return again before the show closes.

That way, I can take closer looks at, say, the detailed, precise, glowing renderings of the doorknobs, the still lifes with the classic Dutch-style black backgrounds, the flowers and trees and revisit the fascinating gallery of unfinished paintings from the impressive painter who I’d never heard of before Gracie brought his work to Lincoln.

“The Aching Beauty of It All” is on view at Elder Gallery in NWU’s Rogers Fine Arts Buiding at 5000 St. Paul Ave. through Jan. 30. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesday through Friday, 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday and Sunday.

____________________________________________________________

Above: Walter, 1999. Oil on Panel, 10 1/2 x 5 1/2 inches. Portrait of Walter Hall, author of "A Personal Remembrance" seen below.